Egg Foo Yong has a deliciously confused identity. It's not quite an omelet, almost a pancake, and somewhere beyond a fritter. It has become a...

Read MoreThe Egg Foo Yong Story

A few months ago, I had the great pleasure of collaborating with Nom Nom Paleo on a magazine piece about egg foo yong. The magazine went kerfluey and the story never got published, but I wanted to share it with you. Dig in!

Things weren’t often exotic in rural Pennsylvania. I was seven years old, and my family lived in Orwigsburg, a small town tucked in the mountains between Amish farm country and smoke-tinged coal mining towns.

Sometimes on Saturday afternoons, my dad would pack us up in his ‘74 Cadillac Deville and steer us north on Route 61 to the Chinese restaurant in the next town over. Its storefront was rimmed with gold filigree, and red dragons slithered up the doorframe. To peer into the display window, we had to get close — nose-touching-the-glass close. It was amber from the perpetual grind of the grease and fogged with moisture. The smell of hot, fried things hung in the air.

Standing on my tiptoes for leverage, I saw a stack of crispy pancakes piled on a tray inside. I’d already decided to order my standby favorites — won ton soup, spare ribs, and plenty of fried noodles with sticky-sweet, apricot-colored duck sauce – but I watched with curiosity as another customer pointed to the stack of egg foo yong. The fritter-like patties were piled on a plate, and then buried under a blanket of thick, brown, shiny gravy. The cook casually threw a handful of sliced scallions on top with one hand, as he passed the white china plate off with the other. The food looked weird and appealing and confusing all at the same time; I’d never seen anything like it.

What the devil is egg foo yong?

Egg foo yong has a deliciously confused identity. It’s not quite a fritter, almost a pancake, and somewhere beyond an omelet. It’s an American dish, but its culinary roots reach back to Shanghai, and its name is Cantonese, with at least six accepted spellings including egg foo young, egg fooyung, egg foo yong, egg fu yung, and egg furong.

For the sake of simplicity, you may think of it as a deep-fried omelet. It starts with lightly beaten eggs that are mixed with a variety of Chinese vegetables, the exact medley and quantity of which are up to the discretion — and available leftovers — of the cook.

Some purists insist on the crunchy triumvirate of water chestnuts, celery, and bean sprouts — but carrots, cabbage, peas, and chopped broccoli have been known to make an appearance. Cooked, diced meats — shrimp, chicken, ham, or bits of crispy-chewy pork char siu — dot the omelet like confetti. If it’s traditional, it’s served as small, “pancake-like rounds of egg swimming in a rich brown gravy,” as The New York Times described it in 1936.

Even as a kid, I wondered how the Chinese family I saw working in that restaurant ended up in “nothing new ever happens here” coal country. They were so foreign (and, therefore, intriguing and attractive). To understand how foods like chop suey and egg foo yong, along with the people who ate them, landed in my somewhat sheltered corner of Pennsylvania, I had to go back to the California Gold Rush. (Cue the old-timey piano music and sepia-toned photographs of mid-nineteenth century Barbary Coast.)

From Canton to California

In the 1850s, the California Gold Rush attracted fortune seekers from all over the world, including Chinese immigrants from Canton, who used their traditional cooking skills to operate the first hole-in-the-wall Chinese restaurants. Called “chow chows,” these eateries catered primarily to their Asian brethren. Americans were suspicious of the unfamiliar flavors and textures of China’s nose-to-tail approach to cuisine. Eventually, the Chinese cooks learned that to appeal to American palates, they could disguise animal bits within golden-fried, friendly packages.

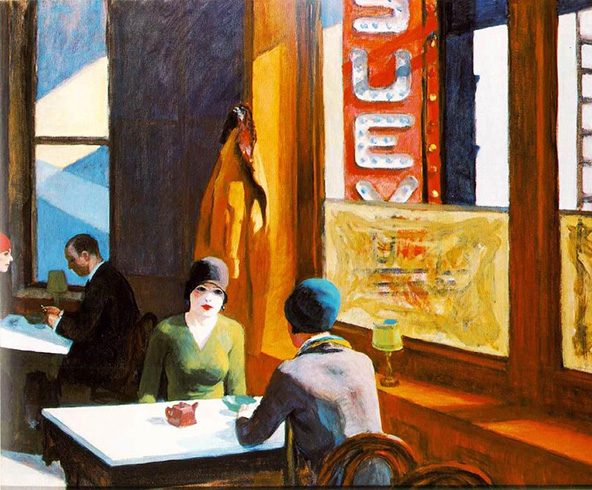

This Americanized Chinese food began to migrate east, taking new tastes to neighborhoods across the United States. In 1929, painter Edward Hopper, know for immortalizing small moments of pure American-ness, depicted stylish women in cloche hats in a chop suey shop.

Then, during World War II, China became our ally, and suddenly, Chinese food was not only accepted, it was glamorized. It became the taste of adventure and sophistication. Food manufacturer Chun King introduced oversized cans of chop suey and chow mein that suburban housewives could pick up at the supermarket and prepare on their stovetops. Most Chinese joints served their fried rice and egg foo yong alongside all-American dishes like fried chicken and crab cakes. Chinese food had arrived in the heartland.

In cosmopolitan coastal cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C., formerly down-at-the-heel Chinatowns became chic destinations. New York City quickly became a hotbed of Asian culture, adding authentic Hunan and Szechuan eateries to the ubiquitous, greasy, Americanized Chinese diners. “Going for Chinese” became the thing that cool cats did with their hip friends. According to lore, a meeting over Chinese food at Washington, D.C.’s Yenching Palace helped settle the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.

All of this history and trivia cleared up the mystery of egg foo yong’s origins, but I was still curious about the experience of the people who made and ate the food. Then my friend Henry Fong, a Chinese-American, told me about Fong’s Chop Suey.

A Fong Family Affair

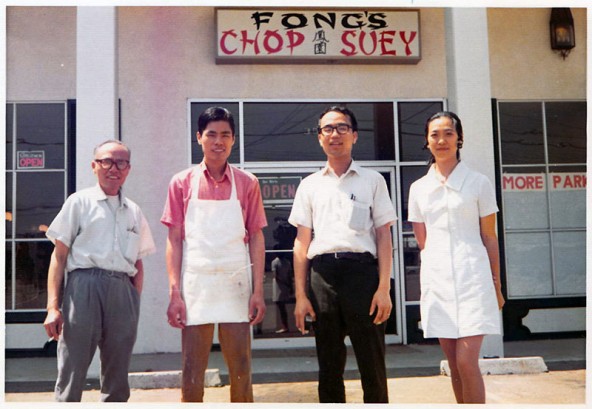

Situated about 20 miles east of San Francisco, Castro Valley was, in 1972, predominantly white, conservative, and middle class; ethnic restaurants were scarce. But the patriarch of the Fong family had emigrated from Hong Kong a decade earlier with a dream. “My dad thought of America as a land of opportunity. He wanted to open his own business,” said Henry, who grew up in the family restaurant, Fong’s Chop Suey.

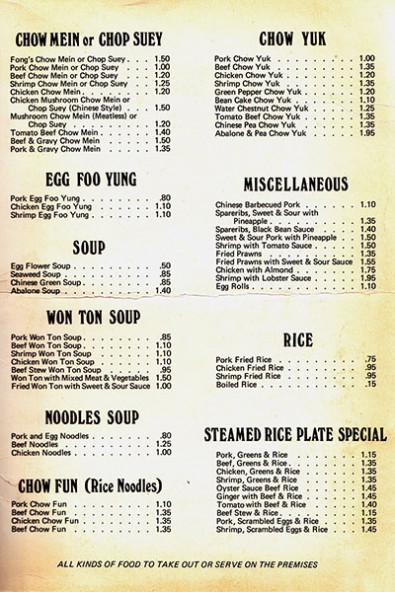

Henry and his cousins played hide-and-seek under tables in the dining room and practiced baseball in the parking lot. When they were older, they were put to work: peeling vegetables, shelling beans, de-veining shrimp, washing dishes, manning the deep fryers. Their reward? Unlimited access to everything on the menu. “I loved the stuff,” Henry told me. “There was nothing better than a big bowl of sweet-and-sour pork with canned pineapple, on top of a steaming scoop of white rice.”

Our talk turned to egg foo yong, and Henry reminisced about the irresistible modification of his heritage. As it turns out, egg foo yong was a special treat for him as a child, habitually prepared by his father, rather than stir-fried by a hired cook.

Opening day at Fong’s Chop Suey.

Opening day at Fong’s Chop Suey.

The troupe of cousins would follow Henry’s dad into the walk-in refrigerator where he’d crack dozens of eggs into a large plastic tub, followed by handfuls of bean sprouts, flour, salt, and spices. With the kids gathered around the flattop griddle, scoops of batter were ladled onto its greased, sizzling surface to form individual pancake-sized patties. Before the batter could set, diced pork, beef, or chicken was sprinkled on its surface, then the patties were browned and packed away into the refrigerator to wait for customers’ requests.

“But every so often,” Henry remembered, “we’d get a fresh batch to share, right off the griddle. Forget the brown gravy! I just loved biting into the savory, springy, meaty egg patties.”

Years later, when Henry met his wife Michelle, she visited Fong’s and encountered egg foo yong for the first time. Unlike her soon-to-be-husband, she’d grown up in a Chinese family that avoided Americanized Chinese fare, dining instead on the “real stuff.” Henry said that she also turned down the brown gravy (“That’s when I knew we were meant for each other.”) and after her first bite, she laughed, “It’s like an omelet crossed with a pancake.”

In 1998, after 26 years of serving Chinese food, the Fong’s sold their restaurant. Although the new owners kept egg food yong on the menu, Henry never ate it there again. “To me, it was special only if you got to see it made.”

Now Michelle has whipped up her own version of egg foo yong. Loaded with spinach and ham, it’s an even more Americanized version of this American hybrid. Her two sons, compact versions of Henry, stand eye-level with the countertop as she ladles batter onto a hot griddle. Henry — watching his sons watch the patties brown on the griddle — looks a little dreamy. “That’s my kind of comfort food.”

Take a bite of my recipe for Paleo Egg Foo Yong.

References

As always, my heartfelt gratitude to Michelle and Henry for their friendship, warm heart, and open collaboration. These are the history sources I used to learn more about the history of Chinese food in the United States.

Beard, James. James Beard’s American Cookery. New York: Little, Brown; 2010.

Chin, Victoria. “A Taste of History, Chinese Style.” UCLA Asia Institute (July 7, 2005)

Coe, Andrew. “Chinese Brown Sauce: A Detective Story.” The Atlantic (July 8, 2010)

Coe, Andrew. Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009

Lee, Jennifer 8. “Jennifer 8. Lee hunts for General Tso.” TED Conference (July 2008)

Lee, Jennifer 8. The Fortune Cookie Chronicles: Adventures in the World of Chinese Food. New York: Twelve; 2008.

Luo, Michael. “As All-American as Egg Foo Yong.” The New York Times (September 22, 2004)

So, Hemmy. “Reading history in Chinese menus.” Downtown Express Volume 17, Issue 19 (October 01 – 07, 2004)

Still hungry? Try these

Confession #1: In the midst of purging our stuff and preparing for the movers and dealing with the disruption caused by a string of people...

Read More

This is *wonderful*, I’m sorry to hear that it wasn’t printed.

Oh! You’re so nice… thank you! I’m entering it in a sort of writing competition, so hopefully I’ll have good news about that some day. It’s a long shot, but I’m kind of excited about sticking my neck out to try it.

Great writing! My mom told me that, after a night out, my grandparents used to drive to Baltimore to get Chinese food (prior to interstate 95 going in it was probably a 45-60 minute drive). I grew up going to the one Chinese restaurant in my town, where as a little kid the owner would take me back into the kitchen to watch the staff cook (and to eat as many freshly made fortune cookies as I could hold). I love Americanized and authentic Chinese food, even my other grandmother’s chop suey recipe (she was from Vermont!).

I will try these for sure… funny, all these years I thought egg foo yong was a noodle dish.

Thanks for the story! I recently read the winter 2012 “The China Town Issue” of Lucky Peach magazine (journal of food writing). This would have fit right in! This is in no way a sponsored comment, btw. I would love to see your writing in that magazine in future; its one of my favorites. 🙂

I’m flattered — Lucky Peach is a great magazine. I love it, too!

I picked up your book last week in prep for a W30 challenge, started Saturday. I made this for breakfast yesterday and enjoyed it so much I made it again today! So delicious and I am happy I came to your site to check it out so I could read the story as well. I am cooking my way through the book and love your site, thank you!

Such a nice comment — thank you! And thanks for buying Well Fed! Congratulations on Whole30-ing… hope it’s going well so far, and really glad you liked the egg foo yong. Have fun with Well Fed!

I just got Well Fed in the mail 2 days ago and cannot wait for the weekend!

Every Sunday I do my own “cookup” and I’ve never know it was a thing! Anyway, I’m excited to try this recipe out.

P.S. Orwigsburg is not far from me (Harleysville)!

Happy cooking, almost-neighbor! 🙂 Hope you enjoy the new recipes.

What a great article full of the information I am looking for about this very fun egg dish. I am invited this week to supper club and egg foo young is on the menu I will have the most interesting ‘facts’ to share with the other ladies. Thank you!

How fun! Hope you dazzle everyone with the fun facts 🙂

As the British ex daughter in law of two Hong Kong chefs I’m used to foo yong being basically well cooked scrambled eggs with added whatever (chopped green beans…mmmm) so it’s really interesting to see the American version…I’ve never seen anything like it 😉

Give it a try — it’s tasty!

{picking a random post on which to comment}

Melissa, I love your blog and I LOVE your writing. God bless you, Hon! I’m on Day 4 of my first Whole 30 and I couldn’t–I couldn’t!–do it without you.

Well, aren’t you just the nicest ever! Thank you so much — I’m really glad you like my blog and are finding it helpful. CONGRATULATIONS on taking on the Whole30! I’m doing it right now, too! It feels good and difficult in equal measure, which seems about right. Keep me posted on how you’re doing! Hope you have an awesome month.